It’s Worse Than You Think: Please Stop Eating Animals

All animals are beautiful, but some especially. Gwen’s image, White-bellied woodstar, Wayquecha, Peru

Food is more than fuel. It’s comfort, community, and tradition. It’s a pleasure three times a day and a wonderful reprieve from everything else. But pleasures like these are the easiest targets of misinformation. We have been sold a lie. “Doctors smoke Camels.” “Guinness is good for you.” “Got Milk?” “Humanely raised.” We have always bought stories which make us feel good about our comforts. We all want to feel good and nourish our bodies. We all want our kids to be as healthy as possible.

So why do vegans want to ruin a good thing? It’s uncomfortable, it kills the vibe, and we all just want a nice meal before returning to the stress of the rest of life. The simple reason is that the science is in. Animal agriculture is destroying the climate and our health, and it cheapens the ethics of our culture. The evidence isn't subtle. Changing what we eat is the single largest impact normal people can make on the planet and its inhabitants. My goal in this blog post is to present this evidence, backed by clear data visualization, that the exploitation of animals for our consumption is categorically wrong on three levels.

Animal agriculture is the major mitigable source of our climate disaster- not just in terms of carbon emissions, but also deforestation, water misuse, and ecosystem collapse.

For pretty much everybody, it is not necessary for one’s health to consume animal products. For those people, eating animals and their by-products is wrong. Animals have a real perspective with which they understand and relate to the world, just like us. Strong science backs this up. That’s what makes killing them wrong.

Our health, on both a personal and societal level, is negatively impacted by animal products. Heart disease, diabetes, and cancer are all significantly lower in vegan individuals, with a clear causal basis. Animal husbandry is a public health disaster. In a vegan world, there would have been no coronavirus, bird flu, swine flu, or even HIV. All of these diseases, which have devastated millions of lives, were contracted from slaughtered animals; plant to human transmission of disease is comparatively trivial, with notable examples like E. coli passing to lettuce through animal manure. Vegans put on muscle just as easily, and not drinking dairy milk shows no negative effect on bone health.

Those three points make up the short version of this article, but the specifics below draw on data to prove these points to you. The rest of this article is long- I want you to treat it as a resource you can bookmark and return to, because in sum the message is dramatic and worth your time. I also want to emphasize that the point of transitioning from animal products is to reduce animal suffering as much as possible for those who can make the change. This is not directed at those living in food deserts, certain indigenous communities, or people with certain very specific health conditions. Those situations require more nuance. I am also not advocating for a global solution, necessarily. This article is aimed at you, the reader, and the choices that you and I can make right now as individuals to help our planet and all of its residents.

Already sold? Make the change!

I think most people get hung up on decision paralysis of the lifestyle change and taste. Vegan food is also indulgent and tasty! If nothing else, try some new recipes from one of my favorite food bloggers (1, 2, 3) you’ll be surprised at how good and easy it can be. The nutrition plan is easy- eat vegetables, beans, and whole grains and supplement B12, D and omega-3 (meat eaters should probably be supplementing D and omega-3 already). If you work out, add some tofu, seitan, soy curls, or protein powder. Most Americans eat way too much protein- the current protein marketing fad is complete junk- but there are tons of fun and cheap protein options at the Asian grocery store (check the freezer section too for mock meats!). Eating out is easy at Indian, Chinese and Thai restaurants as well as Chipotle, Taco Bell, and Cava.

Home late and need a quick meal? Put brown rice, lentils, or quinoa in the Instant Pot or rice cooker. Take any vegetables and toss in a bit of oil, smoked paprika, garlic powder, salt, and pepper. Cut a block of tofu into four slabs and put them on the skillet with some oil and fry both sides of each. Even easier: get some TVP (in international markets for cheap as carne de soya) and rehydrate in broth or water. Add it all to a bowl or tortilla with some salsa. Feeling ambitious? Cut an onion and some garlic and fry in some oil for a couple of minutes, and add some beans and spices. Easy and cheap! If you mess up, the worst thing that can happen is you eat some kind of raw vegetables or have to scrape the bottom of your pot - no food poisoning to worry about.

Now to the meat of the argument:

Climate:

The climate argument can be separated into three pillars of its own: land use, water use, and net carbon emissions. Everything underlined is a link to data.

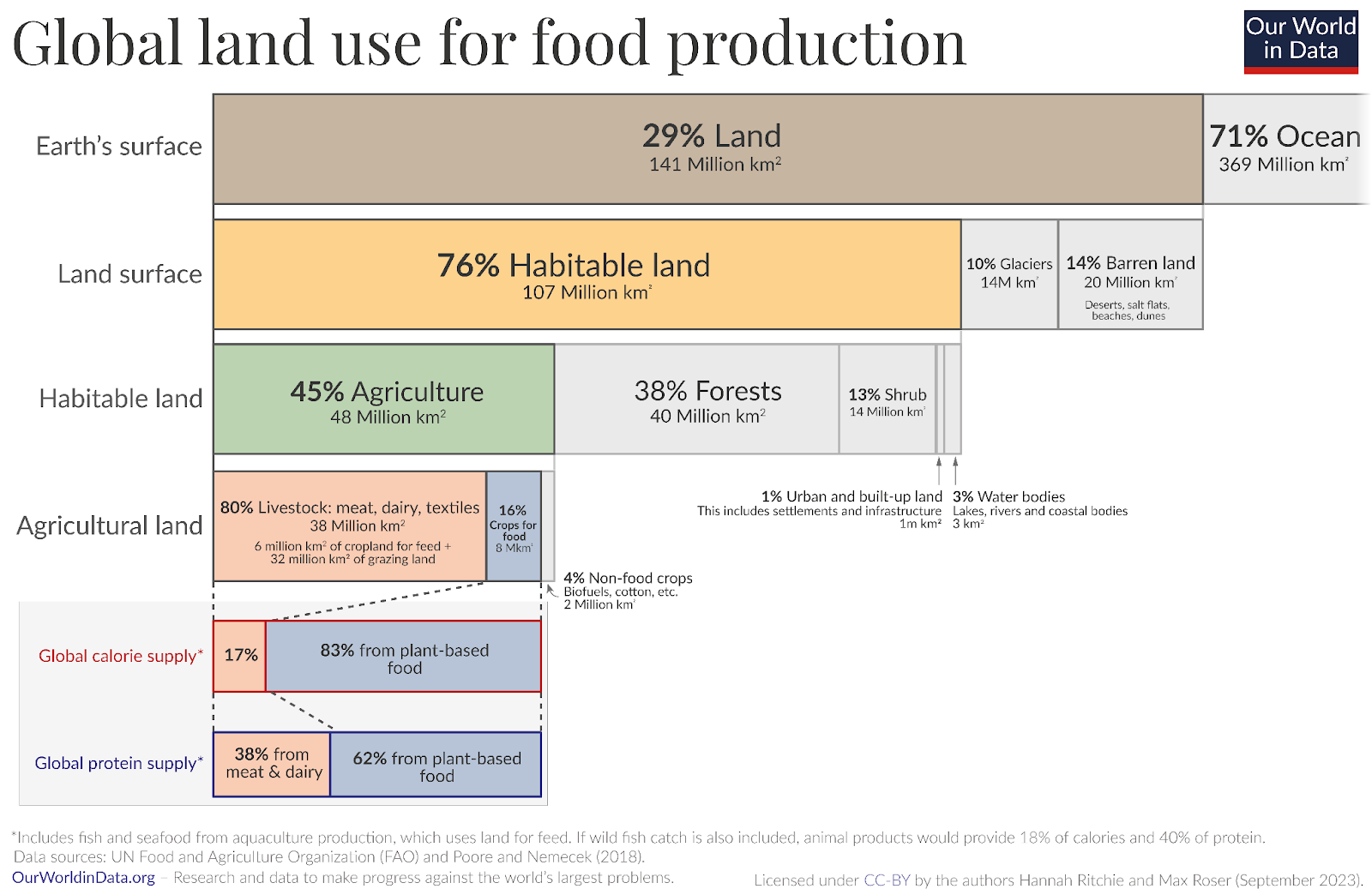

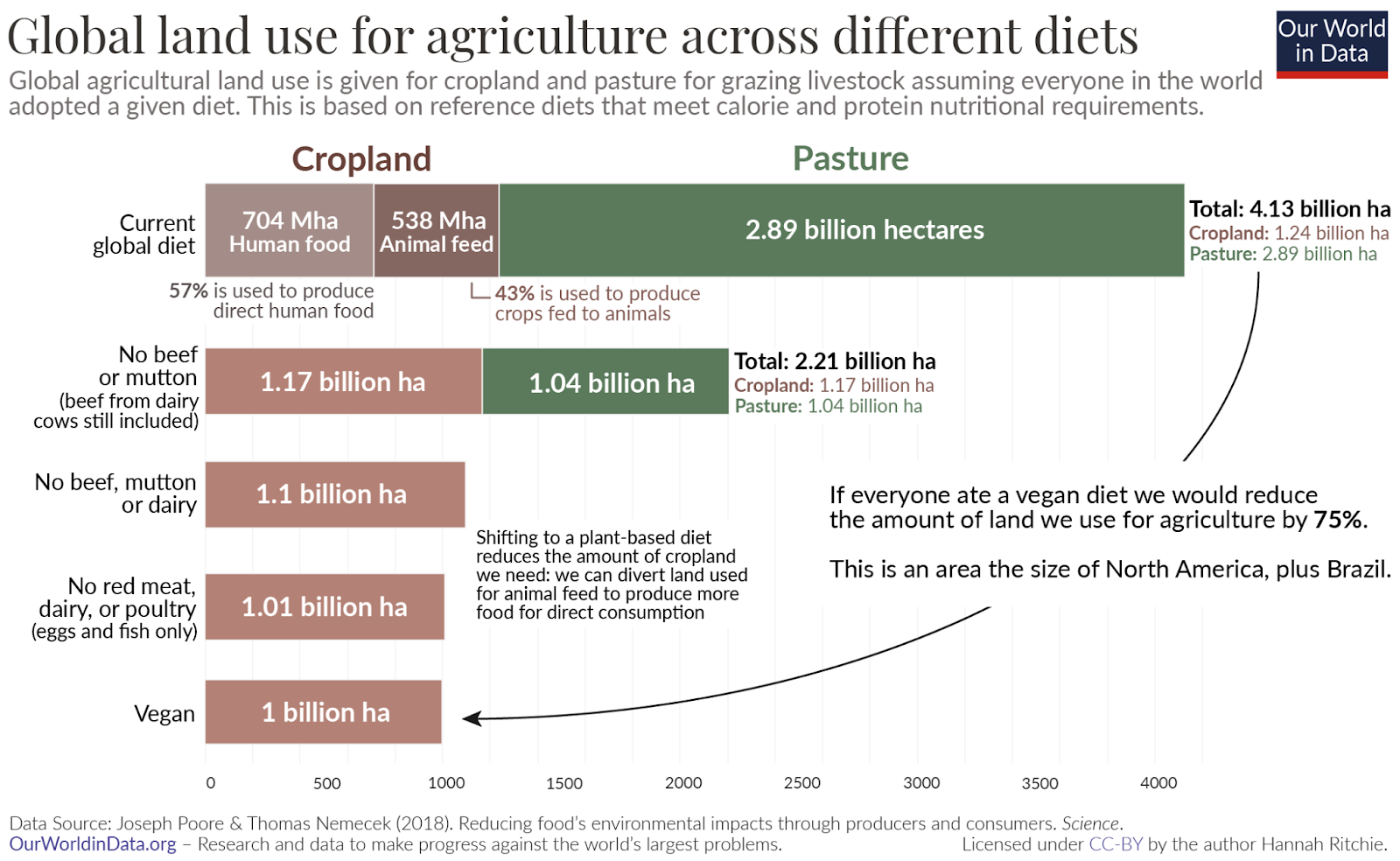

The core of the climate argument is that most of the impact the animal agricultural industry has on the environment is through the plants that feed those animals. 70-80% of the world’s farmland is used to feed animals, and we could feed the same amount of people, with better nutrition, with a quarter of the land which has been devastated from its natural form for agriculture. This equates to 40% of the world’s habitable land, wasted on producing animal products. When we think about the Amazon being deforested, many people have the incorrect image that it’s all going to lumber, or paper, or mining. But the primary driver is cattle pasture and the soy used to feed those cows (bonus: this paper also alludes to a Catch-22 in the argument for more “climate friendly” meat- it necessitates packing more animals into smaller spaces with more intensive agriculture, intensifying ethical concerns).

The following graphs primarily come from the absolutely fantastic data visualization work of Dr. Hannah Ritchie who expertly summarizes a bevy of studies. To see her articles for yourself instead of my summaries: summary dashboard (use the drop downs), land use (and here), emissions + the myth of “good local meat”, and water use.

Land use

How many wildlife documentaries end with images of factories being built, forest being cut, and cities sprawling ever farther? These all contribute, but I can’t think of any which singled out the far and beyond number one cause of destruction of our planet’s limited habitable land: animal agriculture. To get a better image of how our current agricultural landscape is shaped, we can look at visualizations created by Dr. Ritchie based on an article in the journal Science from Oxford investigators Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek.

Our planet hosts a limited amount of habitat for life- perhaps the only location of life in the universe. Yet, nearly 40% of all land that is suitable for life is “developed,” chopped, and planted to feed not us, but a handful of animal species which we like to eat. Even with all this land put towards animal agriculture, animal products provide only 18% of our total calorie intake, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. The same report predicts that according to current demand trends, meat production will double by 2050, which is corroborated by researchers at UC Santa Barbara, published in Nature Sustainability. With business as usual, that spells the end of our planet’s only remaining forests. And we could get farther on far less- read on to see why we only need about 25% of our current farmland to feed humanity on a vegan diet. This is land that used to be home to the biodiversity of the only known planet with life- forests aren’t being chopped for paper, wood, or mining, they are being chopped to make room for for meat, eggs, and cheese.

The scale of the waste is immense, with wide reaching consequences. Among 5,000 sample mammal, bird, fish, reptile, and amphibian, species tallied by the WWF (wildlife, not wrestling), populations have decreased 73% in the last 50 years alone. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the world’s foremost bird research center, this amounts to over 3 billion bird deaths since 1970 - a loss of 30% of all individuals - just in North America. 10% of all insect species - the basis of many ecological food chains- go extinct every decade. Given the data we’ve just seen, this should be no surprise. Animal agriculture by itself has accounted for the loss of ~35x as much habitat destruction as urbanization. In fact, there is as much land currently used to feed animals as there are forests left on our entire planet.

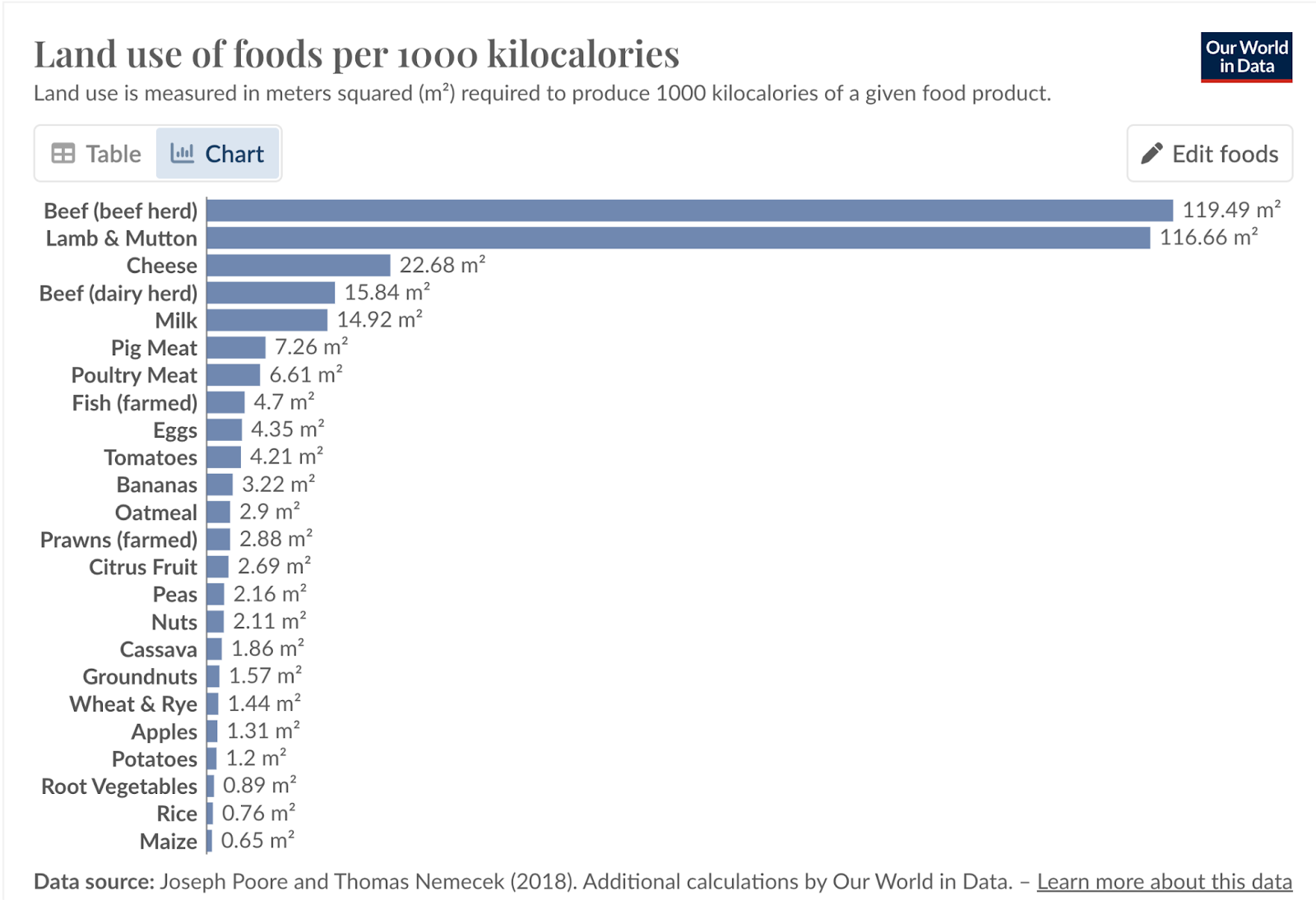

How is this land use distributed among different animals and plants?

Ruminant mammals dominate, by a large margin, with free range cows being the worst offenders. Beef and lamb use over 100 times as much land as plant sources of protein. This begs the question, though- if animal products use so much land, wouldn’t we need just as much cropland to replace it? The answer is a resounding no.

As mentioned, most land used for plant agriculture- 80% of it- and is made up of soy, corn, alfalfa, and the like used to feed cows, chickens, and pigs, not humans. We would need a fraction of our current farmland- conservatively less than 25%- to feed our current population with plants alone. We should also understand that all animal-based foods use more land than any vegetable foods on a calorie basis (excluding seafood, though the ecological footprint of fish is also massive for different reasons).

The story goes, well summarized by this influential report from UC Davis, that the United States’ beef is different, because it comes from grasslands that the U.S. Department of Agriculture deems “marginal.” That is, not good for growing crops, but good for raising cattle. “This means we can take land, which isn’t suitable for much, and make it useful,” so says Frank Mitloehner of UC Davis, an academic superspreader of misinformation on animal agriculture who has received millions in payouts from the meat industry. Firstly, this presupposes that we should exploit all of our world’s wild lands to make them “useful” to us through development. Cattle grazing is the primary driver of the loss of biodiversity in the American west where 70% of land is used to graze. Cattle congregate in ecosystems around rivers, the most ecologically diverse and environmentally consequential points of the ecosystem. The article claims, and I’ve heard repeatedly, that current cattle populations have matched historic bison populations, said as a positive thing.

The spectacular Gunnison Sage Grouse is the most recent victim of ecosystem collapse in America’s grasslands as a result of the demands of animal agriculture. Image credited to US DoI

But cattle are not bison- birds dependent on grasslands have been pushed to the fringes with prominent examples like the Gunnison sage grouse of Colorado numbering less than 4,000 now. Pronghorns are increasingly relegated to protected national forests, and the predators of America’s native grazing animals- bears, wolves, and cougars- have either been extirpated, as American grizzly bears, extinct like the eastern cougar, or kept to extremely limited ranges like wolves and western cougars. Of course, cattle grazing limits plant biodiversity as well and, in turn, the pollinators that rely on those plants (also see: FAQ on bees). Soil and water quality have also been degraded to record lows, and these river ecosystems are the same that feed the megacities of the American west. Eating beef is incompatible with environmentalism.

More on water use later, but as a spoiler: California currently reports that 47% of the state’s scarce water reserves are drunk by cows, compared to just 3% to humans. By reframing what land is for- economic production or environmental stewardship- it becomes clear that pastureland is not monolithic in purpose. In short, simply claiming that pasture cannot be converted neglects both the agronomic potential of improving degraded land for cropping and the environmental value of letting it remain or revert to a wild state (much pasture land actually can be used for plant agriculture). On top of improving biodiversity and protecting endangered animals, re-wilded land becomes a sink for the rest of humanity’s carbon emissions.

The land use argument also holds against any criticism of plant agriculture. If we care about animals killed when crops are harvested, human labor exploited in agriculture, or the land used to raise plants, we should choose the system where the plants we grow are fed to humans. Let’s imagine a world where a state like Illinois is rewilded with beautiful forests and prairies instead of an endless sprawl of farmland.

We share this planet with billions of others of thinking, feeling animals. If you have ever felt awe at a wildlife documentary, a zoo, or a walk in nature, you know that we have pushed the world’s natural beauty to the fringes- a decreasing number of places simply too inconvenient so far for human exploitation. Based on this data, we should understand that wildlife populations are threatened worldwide because of animal agriculture, full stop. If you have ever felt despair at endangered species, there is a change you can make towards a positive future and make a step towards reclaiming 40% of the Earth’s habitable land. We can help the world grow back from our endless exploitation, and we can stop killing 90 billion land animals a year for nothing other than a fleeting meal.

Is this the world we want? Nebraska used to have thriving woodlands and grasslands. We killed billions of animals (and many humans) so we could eat more cows. In a vegan world, 80% of the wilderness could return. Image credited to Markus Spiering

Greenhouse gas emissions.

Now, let's address what most people think of when they think of climate change - greenhouse gas emissions- an impact that extends far beyond the oversimplified "cow farts" narrative that often dominates discussion of this topic. To put it straight, the removal of animal agriculture alone has the potential to stabilize global climates. Professors Dr. Michael Eisen and Dr. Patrick Brown, both current or former HHMI investigators, argue that the elimination of animal products is enough to potentially provide half of the emission reductions needed to meet the Paris Agreement's target of limiting warming to 2°C. Eliminating animal agriculture would reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to 68% of current CO2 emissions through three mechanisms- stopping direct emissions of methane and nitrous oxide from livestock, substantial CO2 emissions from the industry's operations and supply chains, perhaps most importantly, allowing natural ecosystems to recover on the vast tracts of land- again, 40% of habitable land on Earth- currently dedicated to grazing and feed production.

The impact would be particularly significant in the near term, as the study shows that a 15-year global phase-out of animal agriculture would effectively freeze the greenhouse gas warming potential of the atmosphere for 30 years. This rapid impact is largely due to the unique atmospheric chemistry of methane (yes, the cow farts), which is the primary greenhouse gas produced by cattle and other ruminants through their digestive processes. While methane is roughly 84 times more potent than CO2 over a 20-year period, it has a relatively short atmospheric lifetime of about nine years. This is in comparison to carbon dioxide, which follows a complex cycle where roughly half remains in the atmosphere for centuries to millennia, cycling between various carbon sinks.

Beef production alone accounts for 47% of the climate impact from animal agriculture, with beef and dairy from cattle and buffalo collectively responsible for 79% of the total impact. Perhaps most striking is that ruminants, meaning cattle, buffalo, sheep, and goats, and including by-products like milk, provide less than 19% of the protein in the global human diet, yet account for 90% of the climate impact from all livestock. This massive disparity between nutritional contribution and climate impact points to an obvious opportunity for climate action - particularly given our ability to meet all our nutritional needs through plant-based sources, which we'll explore in detail later.

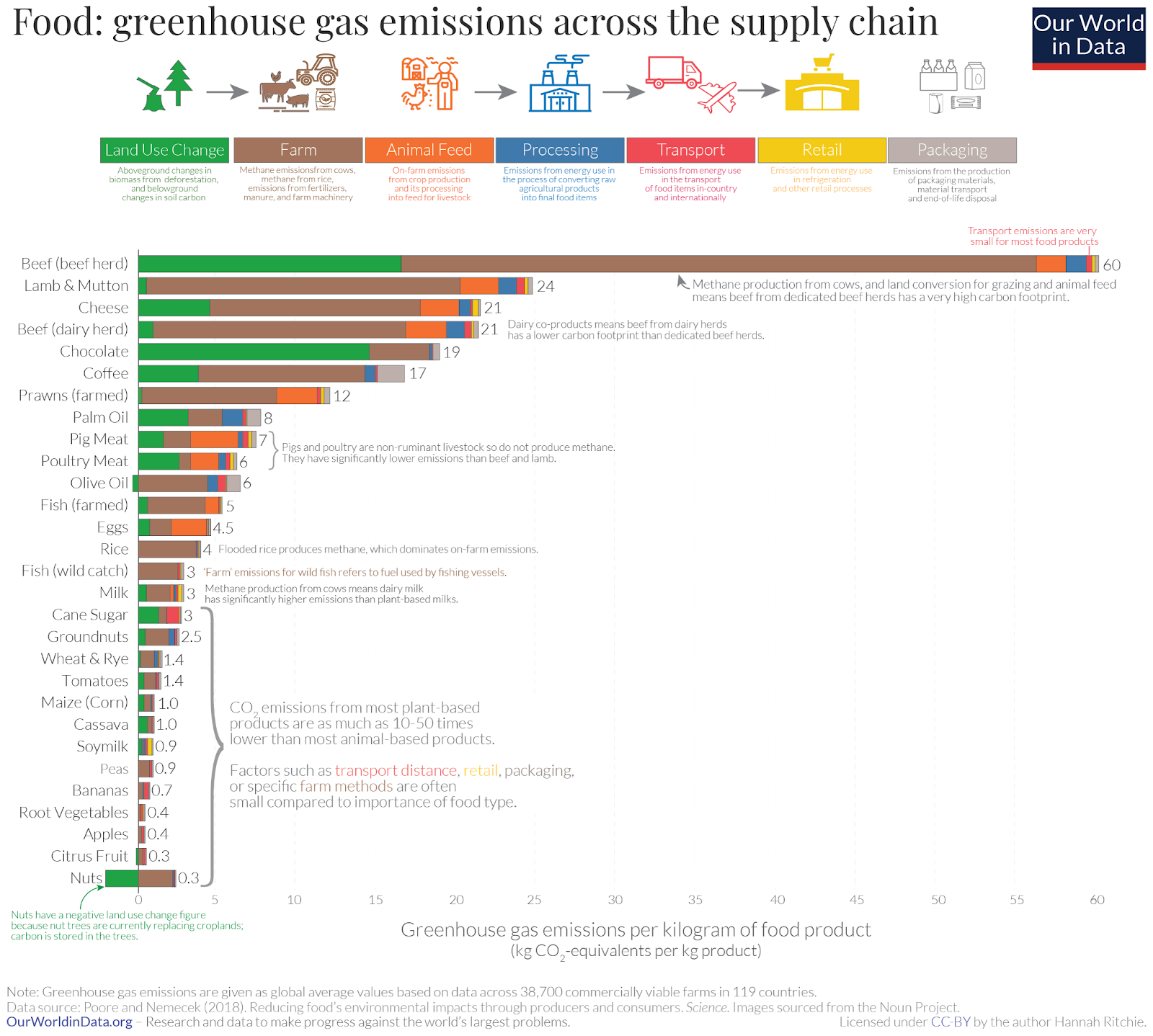

Once again, the best graphics are created by Dr. Hannah Ritche:

With this data, which measures the emissions per kilogram of product (see for yourself which trends hold when we measure per calorie or gram of protein) we can immediately dispel some oft-repeated myths. Clearly, transportation is a very small part of the picture, which casts away the idea that eating local is dramatically better than eating imported food- it is a vegan rite of passage to be asked about the climate impact of avocados from Mexico. The amount of emissions from the production of the food dominates the amount from transportation, across plants and animals.

We also get an idea that land use change - carbon that is no longer being sucked up by the trees and grasslands which covered the farmland before its development- provides a large portion of net emissions. And, this impact is worse for “ethically raised” animals raised on “free range,” which of course require more land per animal. Perhaps frustratingly, part of the emissions cost is actually made better by the most cruel conditions, packing as many animals into the smallest space. Here we can also see that nut trees, some of which are large consumers of water, are net carbon sinks- read: they suck carbon out of the air. There are some plant outliers here like coffee and chocolate, and there is no reason not to scrutinize these plants. However, neither of these are eaten primarily for nutrition, so as far as I am arguing for eating plants as an alternative to eating animals, they are a point independent of the vegan argument.

For seeing how these trends hold up in aggregate, we can look here to see that in the EU, which has fewer emissions per unit of animal product than the US, animal products still contribute 75% of emissions .

Are processed meat replacements any better? Yes. Much better.

An Impossible Burger has 4% of the carbon footprint of beef. It’s no wonder then that them and Beyond were the target of a smear campaign funded by anonymous industry donors who erroneously claimed that processed plant foods are a health disaster. We can live happy, healthy lives without meat- it’s optional and inefficient. We can’t implement a carbon tax overnight and we can’t change our state’s electrical grid. We can make a real impact, three times a day.

Water use

Water usage is often overlooked in mainstream discussions about climate impact, yet data consistently show that animal agriculture is one of the largest drains on our increasingly scarce freshwater resources. In California alone, nearly half of the state’s freshwater consumption is attributed to livestock, compared to less than 5% for direct human use. On a global scale, around 70% of our total freshwater withdrawals are used for agriculture, the majority of which goes to producing feed for animals rather than food for humans. This strain on water resources in arid or highly populated regions can quickly tip the balance from manageable to critical water stress, as defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. While some countries are still in “low” or “medium” stress categories, areas of the United States, along with parts of the Middle East, North Africa, and elsewhere, are already at high or critical stress levels, withdrawing more water than is sustainably available. Local aquifers are stretched thin, threatening long-term water security.

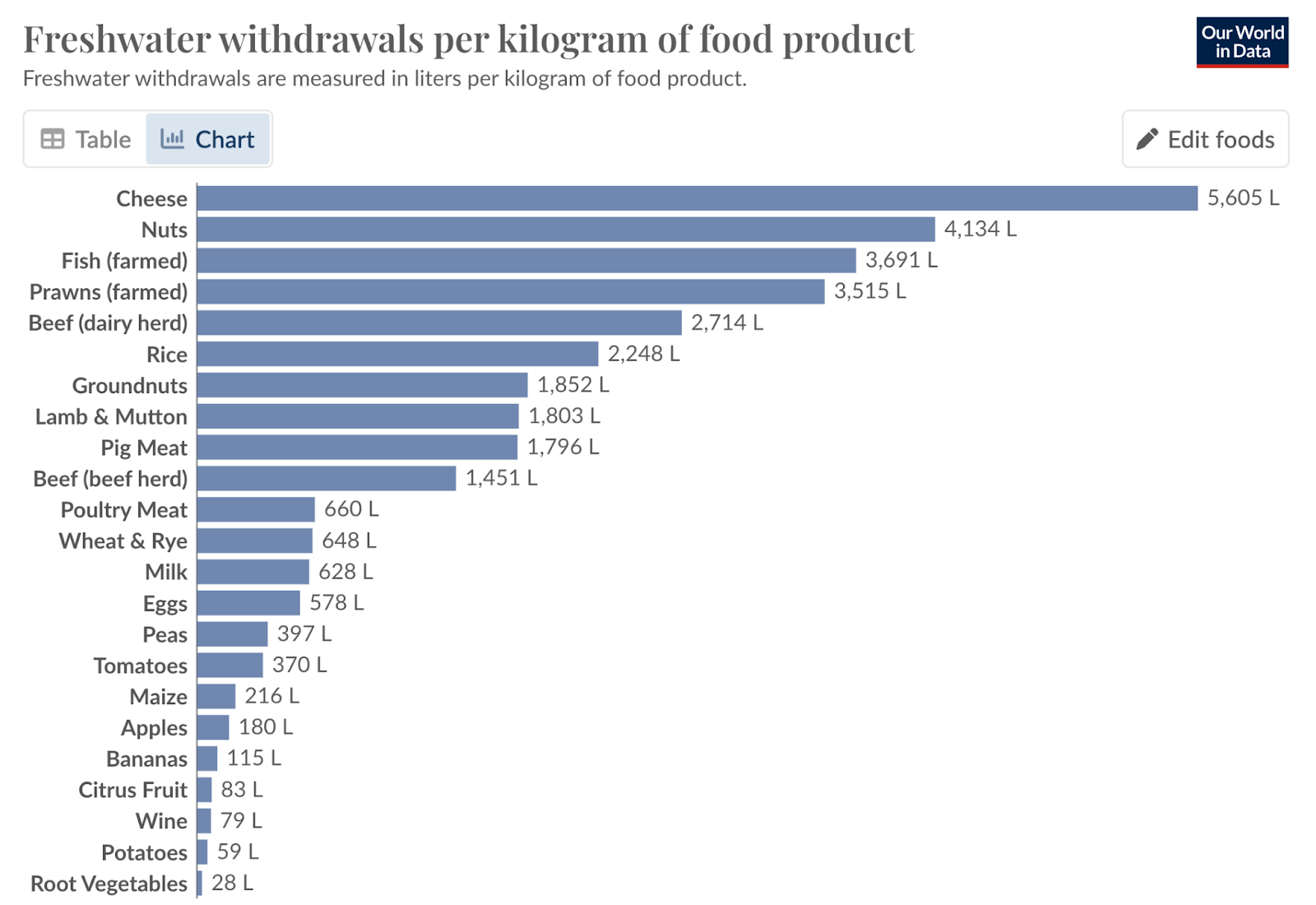

The amount of water used for different food products, once again, tells the same story but with some different worst-offenders. Dr. Ritchie, adapting Poore and Nemecek, once again:

Again, let’s pay attention to the unit being measured here- liters of water per kilogram of food. We can start to see here how our calibration of the water use of agriculture is so off-base. Let’s think about other environmental pushes, like taking shorter showers. Showers use 15-20 liters per minute, so at the high end, a long, luxurious 30-minute shower uses 480L of water, which is the same amount as 3 oz of cheese (calculated from above). But you don’t think about running the shower for three hours when you dump a bag of cheddar cheese into the pot for some macaroni. This gets much worse for products which we eat in larger weights- cereals and meats. Fortunately, though wheat and rye use more water, they are among the smallest in their carbon and land footprint. Rice is actually also one of the worst grain offenders for greenhouse gasses because flooded rice produces methane, but it has among the smallest land usage. Nuts are large consumers of water, especially in water-limited areas like California, but they are net sinks of carbon and use less than 10% the land of cheese. We also must consider the metric- a kilogram of nuts is a lot of nuts, while a kilogram of beef is a weekly purchase for many families, and it adds up with every burger or bowl of ramen.

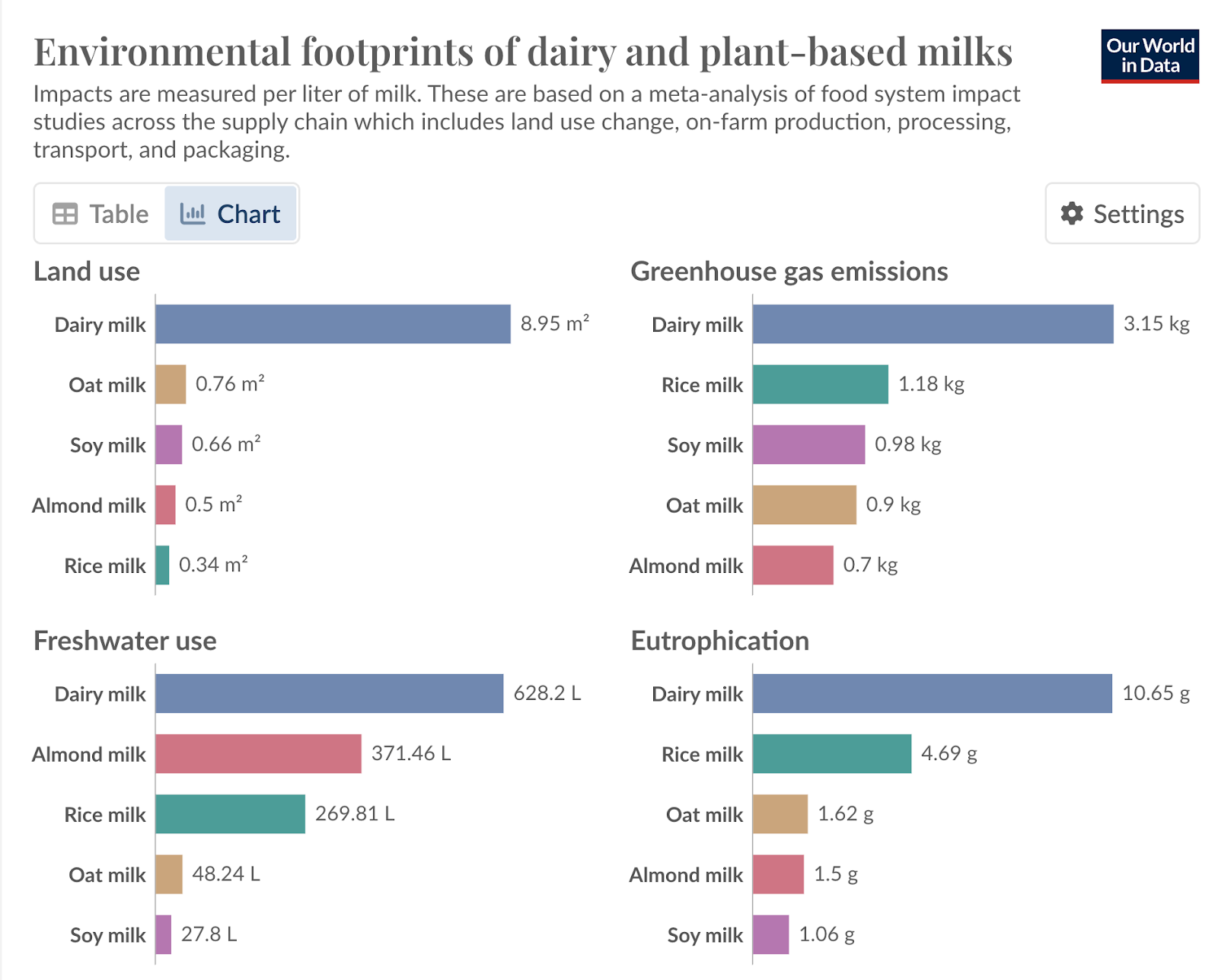

As expected, when we break down across all three axes, we see that the climate impact on land, greenhouse gasses, and water dramatically favors the plant-based replacement, especially land use.

There is a new metric here, though, which should take our interest. Beyond direct overuse of water, animal agriculture also has a large downstream effect: eutrophication. This process occurs when nutrient-rich runoff, often containing manure or synthetic fertilizers used to grow feed crops, enters waterways. The excess nitrogen and phosphorus trigger rampant algae blooms, which eventually decay and deplete oxygen levels in the water, creating “dead zones” that kill fish and other aquatic life. Similar damage can happen when farms store massive quantities of animal waste in open-air lagoons, which periodically flood and leak into groundwater or rivers. As demand for animal products increases, more land is tilled for feed crops, more fertilizers are used, and more manure must be managed, which exponentially compounds these runoff and pollution problems.

Viewed alongside land-use and carbon emissions, the water footprint of our diets underscores the same conclusion: switching away from animal products is one of the simplest and most impactful ways we can live within the planet’s limits. This past week, Los Angeles was on fire, and the hoses of firefighters ran dry. Half of California’s water is wastefully fed, directly or indirectly, to animals. Without water, we die, and they die.

We are not bound to this trajectory. Every meal is a vote for the kind of world we want, and every acre spared from grazing and feed crops can begin to heal. If we accept responsibility and act to end the captivity, breeding, and killing of animals for food, we might write a new narrative in which we share our planet with its other thinking, feeling, inhabitants who, above all, don’t want to die.

Ethics and Neuroscience

Who deserves our respect? Even now, humans belittle, diminish, and slaughter one another- should we waste time convincing others that non-human animals also deserve moral consideration? But I would frame the problem differently. What would we have to change about a human to justify treating them the way we treat animals? What quality in humans makes them worthy of moral consideration? Is it pain? Is it intelligence? We would treat a person who doesn’t feel pain with dignity, and humans who are more or less intelligent (and who decides how we measure intelligence?) deserve the same dignity.

The answer is that all humans and non-human animals certainly feel, understand, and relate to the world, and we do not have to kill them to live, so we should not.

Oppression has always relied on the same principle: power grants permission. In every historical atrocity- slavery, genocide, disenfranchisement- the “trait” supposedly justifying the mistreatment is always arbitrary. The real engine of cruelty is that one group simply has the might to inflict harm on another. Aristotle, for instance, deemed certain people “natural slaves,” just as biblical traditions cast women as property. We can see, in hindsight, that these were rationalizations of a status quo where those who already had power placed themselves on a higher spiritual or moral plane. By dismissing their mistreatment of the oppressed, they convinced themselves that the oppressed must somehow deserve it, whether through original sin, birthright, or lack of capability. What drives me is the idea that in their time, these ideas were culturally embedded. Without some unifying framework for where we place dignity and moral value, how can we be sure that we are actually acting morally and not simply acting in the least moral way our society and our friends will allow? Even in our supposedly enlightened society, which claims to acknowledge the fundamental equality of all humans, we still find ways to rationalize suffering when it serves those in power. Can we recall Reagan rhetoric that HIV is divine judgement on gay people? Will we continue to accept the mass incarceration of Black Americans as simply the price of "law and order" rather than a continuation of racial control by another name? If humans are able to ignore the pain they inflict of other humans, it's no wonder we still ignore the suffering of animals who cannot speak for themselves.

Egrets, once again widespread, were once on the verge of extinction because they were hunted for their beautiful white feathers. Conservation efforts saved them. Can we stop bad practices without legal intervention? My image, great egret on the Potomac River

So, can animals suffer? As humans, we understand that there is a special feeling of being yourself, the feeling to be a thing that observes and relates the world around it, the feeling to have a perspective. That feeling arises from the brain. Feelings of pain arise from signals sent from our body to our brain in order to prevent harm. There are also feelings of pain within the brain- the pain of losing a loved one or the pain of captivity. The animals we eat certainly feel all of the above. This is intuitive to those who own pets and can see the inner world of their dog companions. Why else would you go out and play catch other than to enrich your pet’s life? Why do you cry over a dog more than a broken TV? Obviously we know that these animals have internal lives that are important to them, it’s just a matter of extending our grace and our empathy to the animals we make into victims rather than companions. These animals have a real, tangible perspective of the world. They experience living. Dogs and cats have rich internal lives, and so do livestock animals. The difference in our minds is based on cultural conditioning, not science.

The scientific consensus is growing clearer by the year: animals possess the neurological machinery necessary for suffering, emotional experience, and conscious awareness. In 2012, a group of prominent neuroscientists- including Philip Low and Christof Koch- former president of the Allen Institute, vegetarian and renowned figure in computational neuroscience- convened at Cambridge University and issued what’s now known as the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness. They concluded that many non-human animals “possess the neurological substrates that generate consciousness.” Researchers like Jaak Panksepp, known for pioneering work in affective neuroscience, identified discrete “emotional command systems” in the brains of rats, dogs, and other mammals. Panksepp’s experiments famously showed that rats “laugh” ultrasonically when tickled- a sign of positive affect- and exhibit sorrow when separated from familiar cage-mates.

Anyone with a pet knows that animals love to play- just like we do.

These responses should not be characterized as reflexes: they reflect complex emotional states analogous to our own. Though, this is far from the consensus you would glean from the plates of neuroscientists where I work. Why the disconnect? A lab head at my workplace frequently jokes that “the flies get smarter every year,” as we continue to learn about how such a small animal learns, dreams, holds preferences, navigates complex environments, and more, has a fully mapped brain of 200,000 neurons which perform such complex and heterogeneous computations that even in the five years since the the full wiring diagram was completed, we are still not even close to being within reach of a comprehensive understanding of its decision making.

I don’t necessarily mean to argue that flies deserve equal consideration to humans, but I do want to earnestly ask you to think about what it feels like to be a fly. Because it does feel like something. Flies have about 1000 times as many neurons as ringworms, Mice have about 500 times as many neurons as flies, we have about 1000 times as many neurons as mice, and elephants have 3 times as many neurons as us. What is gained or lost in that difference in scale? The brain itself enables complex computation unlike any other system in nature. We know it feels special, and we know that what separates us from other animals, through evolution, is a gradual process of small changes over time. We readily compare and analyze homologous bone structures in humans, other mammals, fish, birds, reptiles, and amphibians- why do we act as though our brain is in a different category? There is absolutely no evidence that humans have brain structures which generate a presence of experience different from other animals.

One common counter argument goes: “Plants can sense their environment- don’t they have feelings, too?” However, the overwhelming scientific consensus holds that while plants do respond to stimuli (light, touch, chemical signals), plants lack the integrative nervous system and centralized brain structures that produce the subjective feeling of pain. A plant’s adaptation to survive- for instance, emitting chemicals when insects nibble their leaves- does not require consciousness or an inner experience of suffering. By contrast, animals have specific neural pathways and pain receptors sending signals to a centralized organ (the brain), where these inputs are processed into the subjective experience we call “pain.” Plants have simple reflexes which are far exceeded in complexity and information integration by ringworms. Even if plants did feel pain, recall the land use argument- if nearly 80% of farmland worldwide is used for crops to feed animals, we minimize plant suffering through a plant-based diet.

So the core question shifts from “Do they feel?” to “Will we acknowledge it?” Because if animals experience pain, then any argument justifying their oppression comes down to power. “We can kill them- so we will,” sounds alarmingly similar to “We can own slaves- so we will.” In all cases, might becomes the supposed right, and those with fewer defenses are at our mercy. Neuroscientists, who see animal sentience firsthand, don’t tend to be vegan- why is that? I want to quote, with some omissions for length, two sections that have stuck with me on the topic, first from Simon Barnes, an ex-sports-writer-turned-wildlife-journalist for The Times (Britain, not NYC) before he was fired for writing against institutionalized hunting in the U.K., and one from Carl Sagan, famed physicist and science communicat0r.

Carl Safina, a professor of nature and humanity at Stony Brook University, New York, wrote:

Suggesting that other animals can feel anything wasn’t just a conversation stopper; it was a career killer. In 1992, readers of the exclusive journal Science were warned by one academic writer that studying animal perceptions ‘isn’t a project I’d recommend to anyone without tenure’.

It is odd that scientists, who claim to work only from data... operate on the certainty that, while all placental mammals are put together in the same way physiologically, one of them is somehow completely different from all the other 4,000-odd – so different that we don’t even need evidence to prove it. Are we talking about the soul here? I ask only for information.

Throughout the years, people have sought to isolate and identify humanity’s unique selling point, and every time they have done so, they discover that some animal – some non-human animal – has it, too. All the barriers we have erected between ourselves and other animals turn out to be frail and porous: emotion, thought, problem-solving, tool use, culture, an understanding of death, an awareness of the self, consciousness, language, syntax, sport, mercy, magnanimity, individuality, names, personality, reason, planning, insight, foresight, imagination, moral choice… even art, religion and jokes.

It’s all in Darwin, but we have spent getting on for two centuries ignoring or distorting the stuff he taught us. In The Descent of Man, he wrote: “The difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.” If you accept evolution by means of natural selection, that must be true.

Why, then, are humans so resistant to the idea? We can find the answer in human history. For many years it was important to uphold the notion of the moral and mental inferiority of non-white people, because without such a certainty colonialism and slavery would be immoral. And that would never do: they were so convenient.

To change our views on the uniqueness of human beings would require recalibrating 5,000 years or so of human thought, which would in turn require revolutionary changes in the way we live our lives and manage the planet we all live on.

And that would be highly inconvenient.

Humans — who enslave, castrate, experiment on, and fillet other animals — have had an understandable penchant for pretending animals do not feel pain. A sharp distinction between humans and 'animals' is essential if we are to bend them to our will, make them work for us, wear them, eat them — without any disquieting tinges of guilt or regret. It is unseemly of us, who often behave so unfeelingly toward other animals, to contend that only humans can suffer. The behavior of other animals renders such pretensions specious. They are just too much like us.”

But Carl Sagan was not vegan. Neither is Simon Barnes. David Attenborough isn’t, but Jane Goodall was. Knowing that eating animals is wrong, even very wrong, isn't enough to change our habits, though it is possible, somehow. We can simply continue to live with the occasional pang of guilt and a little voice that says “I’ll figure it out eventually” or “eating meat is natural” or “my husband would never go for it.” But the animals are no less tortured, no more free, and no less dead.

Many of us grew up eating animals without a second thought. The shock of realizing we may have contributed to what we now view as mass suffering can be overwhelming, and it is natural to feel guilt or regret. Yet, we have seen collective moral shifts on slavery, civil rights, or women’s equality. History shows that once people begin to see oppression for what it is, change can follow. Progress often comes painfully, sometimes haltingly, but it does come.

I chose not to include any gruesome footage or photography, but I can tell you, it’s bad. If this is something you think would move you, to see the direct consequences of our actions, watch the movies Earthlings or Dominion. They are horror movies in the first degree.

Health and Eating:

Vegan food is healthier on the whole, but it doesn’t have to be any less indulgent. My image, Brammibal’s Donuts

On top of the considerations of climate change and ethics, eating vegan is just better for you. Plant foods contain zero dietary cholesterol (cholesterol is synthesized by animal cells, not plant cells), are vanishingly low in unsaturated fat (only coconut oil and palm oil have any), and, a bonus, they’re rich in vitamins and minerals. A diet rich in vegetables is recommended by every dietary institution on the planet- from the American Heart Association to the World Health Organization- excepting Joe Rogan.

The reason for this recommendation is a myriad of evidence that diets centered on whole, plant foods are consistently linked to lower risks of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and certain cancers. Observational studies such as the Adventist Health Study or EPIC-Oxford show that people who emphasize plant-based diets have lower rates of chronic illness overall- precedence of type-2 diabetes was half in vegans, blood pressure was significantly lower, and 55-year old vegans were found to be, on average, 30 pounds lighter.

It’s also worth noting that most people in high-income countries, especially the United States, already consume more protein than they need. The Recommended Dietary Allowance for protein in healthy adults is 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight (increasing to 1-1.2g/kg around age 50), roughly 50–60 grams per day for someone weighing 150 pounds. Yet the average American intake is often double or triple that. Protein deficiency is practically unheard of outside of severe malnutrition, yet the fixation on protein persists partly because of marketing from the meat and supplement industries. Indeed, from the EPIC-Oxford study, the real challenge for many Western diets isn’t getting enough protein, but rather avoiding excess, which can strain kidney function and may correlate with higher risks of certain metabolic diseases. The simple reality is that focusing on a well-rounded plant-based approach checks all the boxes for adequate protein while steering clear of the high saturated fats and cholesterol that often come along with animal sources. In fairness, vegan diets generally require supplementation of B-12, and vegans are often also lower in iodine, so vegans should be careful to make sure to use iodized salt.

Meanwhile, raising billions of animals in crowded environments poses serious public health risks we rarely talk about. Outbreaks of bird flu, swine flu, and antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria have all been linked to dense livestock operations. Covid-19 and HIV came from animals eaten as game- imagine what a different world we would live in if it weren’t for these terrible diseases! Globally, over half of medically important antibiotics are used on farmed animals, often just to keep them alive in unhygienic conditions. This overuse accelerates antibiotic resistance, making it harder to treat infections in both animals and humans. Public health officials at the World Health Organization warn that without changing our current practices, we’re at risk of a “post-antibiotic era” where common illnesses become untreatable in humans. By reducing or eliminating animal agriculture, we dramatically cut that pipeline of antibiotic overuse and reduce the odds of zoonotic diseases leaping from farms to humans.

I often hear “everything in moderation,” or “I don’t care about losing a year at the nursing home.” That’s fine, it’s up to you, but the way I see it, it’s not a year less at the nursing home, it’s that you’re there a year sooner. Unlike the first two arguments, this argument is not a moral imperative, but if animal products are gutting the planet, turning feeling creatures into casualties, and it’s also healthier to skip them- then “moderation” starts to sound like a polite way of saying, “I’m not ready to try.” Giving up steak, and yes, cheese, is possible, and once you’re certain, it’s easy.

Cooking vegan food is not hard, it’s just a new skill to learn. My image, Shisomen Vegan Ramen

So we come to the part where people say “I just don’t know if I can give up how it tastes.” First of all, this is a skill issue- cooking vegan introduces a new set of techniques, just like cooking any new cuisine. But more importantly, imagine if we applied this argument to any other social issue that is as clear cut as this one. More than 90 billion animals are slaughtered a year for vanity. A fleeting lunch at work, forgotten by the time you close your Tupperware. A shift in diet is an opportunity to really learn some international cuisine! Indian, Thai, Indonesian, a lot of Chinese food, and many rustic Mediterranean dishes are vegan already. I encourage people to think about going vegan as adding rather than subtracting- in my experience leaving the bubble of foods I was raised with, (which was wholesome, tasty food!) I found that the world of food is so expansive once you leave the same three-ish animals whose flesh and byproducts make up most people's plates every day.

Here’s a practical first step: if you are at a restaurant and there is a vegan option, like sofritas at Chipotle for example, that is an atomic decision you can make with no extra effort to make a small change. Think about that- if you have a clear choice to ask for a dish that resulted from dramatically more cruelty than another, why would you ever pick that? Will the chicken really improve your life so much more than the tofu or veggies? Here is a sample meal plan from one of my favorite vegan creators. Here is another article about planning for health, and she has separate articles on each of the major nutrients people are worried about. I also have a recipe sheet where I have over a hundred recipes I’ve made which I update. If you want edit access to add vegan recipes you’ve made, send me an email!

I think the larger issue in people’s minds is the social aspect. You’re invited to dinner with your friends to a steakhouse, and you don’t want to be the squeaky wheel. It’s tough, I know. Making and keeping friends is already hard, and adding another layer of anxiety and potential ostracization to the mix is really difficult. I have no answer for this. I just remember those hokey “stand up for what’s right, even if it means you’re standing alone” signs from my elementary room classrooms. Did anybody else read those? Or are we content to feel like we’ve done the right thing after everybody else has done the hard work?

The data is clear- yet the greatest barrier is the quiet, persistent lie that our actions don’t matter. Indecision asks nothing of you. This feels daunting because it is daunting- to confront a lifetime of conditioning, to admit complicity, to change. But isn’t that the very essence of moral courage? To do what’s right because it’s hard? The next time you eat, ask yourself: Does this align with the person I believe myself to be? The truth that should terrify and liberate us is that we are not powerless.

Animals each have a perspective. They are individuals just like us. They perceive and understand the world around them. They don’t want to die. Let today could be the last day you participate in a system that enriches those who kill for profit. We don’t have to live like this. You will feel better knowing that your thoughts and your actions are one. To not go vegan is to watch our house burn down while holding a bucket of water. I live in fear of being a “bad vegan” who proselytizes and judges. But you’re at the bottom of the article and you need to know: if you don’t make the change, you paying people to torture animals for your pleasure and you are creating real demand for ecosystem destruction. There is no way around it. We must change and convince those around us to change or we will burn.

The animals have no voice but yours. Make the change.

Please comment below or email me at justin at ellis-joyce.com if you have any questions.

The world has enough space for all of us. If we make a simple choice, we can preserve the beauty of the Earth. My image, hoary marmot, Mt. Rainier, Washington

Frequently Asked Questions

“Isn’t fossil fuel use a bigger driver of climate change than anything we eat?”

It’s true that power plants, transportation, and heavy industry are all enormous pieces of the global emissions puzzle, but I can walk and chew gum. That doesn’t mean our food choices don’t matter. Many of us have far less control over how our electricity is generated or how quickly society transitions away from oil and coal, but we do decide what’s on our plate every day. Research suggests that shifting from animal agriculture to plant-based eating could provide about half of the emissions reductions needed to meet Paris Agreement targets. In other words, we need a broad fix for energy, but that doesn’t make diet a minor side show- both avenues are urgent.

“Can’t new viruses still emerge from wild animals, even if nobody’s farming cows or chickens?”

Sure, there’s always a chance humans will catch diseases from wild species when we invade their habitats. But most of the big zoonotic threats-bird flu, swine flu, COVID-19, HIV-have come from raising animals in crowded conditions or hunting them in markets. If we stop breeding billions of animals in these stressful, pathogen-friendly environments, the risk of another global pandemic goes way down. We’d also be clearing land for wild animals to live on their own terms, which means less forced interaction overall.

“What about ‘regenerative’ or pasture-raised beef? Isn’t that more sustainable?”

Some people claim we can raise beef in a way that improves soil health and sequesters carbon. There may be limited contexts where that works (very small scale, local herds). But it can’t begin to meet today’s massive global demand for beef. You also often need significant water and feed supplements, and ruminants still produce a lot of methane. Rewilding open areas with native herbivores—like bison—can bring back ecosystems without funneling so many resources into livestock. For me, that’s the more promising path.

“Wouldn’t going vegan force us into massive monocrops that wreck the soil and the bees?”

Actually, most of the big monocultures—corn, soy, and so forth—are grown to feed livestock, not humans directly. If we get rid of that indirect step (growing plants to feed animals to feed us), we end up needing much less farmland overall. That means more room to grow a more diverse range of crops or to set land aside for wildlife. So if you’re worried about monocultures, cutting back on meat is the fastest way to shrink them.

“Is a vegan diet really healthy for everyone, including pregnant women or kids?”

Major health organizations agree that a properly balanced plant-based diet works at all stages of life. You do have to be mindful of nutrients like vitamin B12, vitamin D, iodine, iron, and omega-3s, but that’s no different than someone else making sure they get enough vitamin D in a northern climate. With fortified foods and supplements, it’s quite straightforward. In fact, plenty of folks who aren’t vegan still supplement for these same reasons.

“Don’t some communities rely on animal husbandry as a longstanding cultural or economic practice?”

Yes, and culture matters. But “culturally embedded” doesn’t automatically mean “morally right.” We’ve left behind all kinds of practices- human sacrifice, foot binding, and other traditions- once we realized they were causing harm. Also, much of the world’s meat isn’t produced by indigenous herders or small farms; it’s industrial-scale factory farming. If the majority of meat today comes from cramped, mechanized systems, then that’s the main problem we need to solve. Cultural nuance is real, but it doesn’t override the broader ethical and environmental issues.

“What about all the people whose jobs depend on raising and processing animals?”

A big shift like this does require transition planning. Nobody’s saying we flip a switch overnight. But just as we plan transitions away from fossil fuels, we can also create new opportunities in plant-based agriculture, wildland management, and other sectors. One possibility is reforesting or rewilding large tracts of land while supporting people who can serve as stewards of those ecosystems, the same way park rangers and conservationists do now.

“Why not just buy animal products labeled ‘humane’? Isn’t that better than going fully vegan?”

If those labels truly translated to a cruelty-free life for the animals- plus no environmental damage- that would be a step in the right direction. Unfortunately, “free-range” or “humane” often just means a bit more space per animal, or a more idyllic label on the packaging. There’s still a slaughterhouse at the end, and you still need huge amounts of land and water. Ultimately, if we don’t need to eat animals at all to be healthy, and we know they suffer, it’s hard to see why we keep doing it.

“But plants are alive too, right? Isn’t cutting a carrot just as bad as killing a cow?”

Yes, carrots are alive in the sense that they grow and reproduce. But plants lack the centralized nervous system that actually produces the subjective experience of pain. They respond to stimuli- light, water, touch- but they don’t integrate this information like even a worm brain would. And, if we’re worried about living organisms in general, the math is simple: raising animals kills way more plants overall because we first feed them massive quantities of grains and soy. So from a “minimize harm” standpoint, eating plants directly is the clear choice.

“I really just love the taste of meat and cheese. Doesn’t that matter?”

Taste is real, and I’m not suggesting you shouldn’t care about it. But when you weigh flavor preference against the suffering of billions of creatures and the massive strain on the planet, that preference starts to look smaller than it once did. Plenty of people end up discovering a whole new world of cuisines- stir-fries, hearty Mediterranean stews, Indian dals- that are absolutely delicious and happen to be free of animal products. It’s less about giving something up than it is about exploring new possibilities.

“Bees?”

On the climate side, honey eaten by humans is a complete disaster. We all want to save the bees, but the honey humans eat comes from a single species- the European honeybee. This bee, when kept in America, outcompetes local bee species since they have habitats which are protected from the ecological pressures of the forest. Thus, local bee species, who actually do most of the pollinating since they evolved alongside those plants, crater in population. Also, bees are highly social, sophisticated creatures. They make the honey for themselves- to steal it is exploitation. Beekeepers commonly kill queen bees who produce “unruly” offspring, and hive maintenance (alcohol swabs, relocation, harvest) kills many bees.

“Fish?”

This almost got its own section, but this is long as it is. Refer to this great blog post if this is the last thing to have you on the fence.

Here we are at the bottom! If you are exceptionally interested, and I encourage you to be, you can look at more comprehensive sources. Animal Liberation by Peter Singer, rightly subtitled “The Definitive Classic of the Animal Movement,” is a prominent touchstone, and it is comprehensive. For a more modern and punchy take, I recommend either of Ed Winter’s books in addition to his Youtube channel filled with measured, empathetic dialogues.